Hello! As you may have gathered from the general gist of the website, I’ve decided to start a good old-fashioned blog. The main use of this blog will be to document my thoughts on various projects, not just for other people to read, but so I can keep track of it myself as projects become increasingly complex. My primary ongoing project is currently a polyphonic analogue synthesiser and you join me about bang in the middle of the development. I have completed the rough design of the synth but there is still much to develop and fine tune, and always more to learn.

As I progress into assembling and coding the microprocessor for the synth, I’d like to have a record of the analogue electronics for myself to reference, as my schematics can’t fit all the theory into the notes. I’m going to aim the content of this to people who know the foundations of synths, (you know what an oscillator, a filter and an envelope is), but don’t necessarily know all too much about the internal circuitry of audio equipment. A basic understanding of electronics (ie what a capacitor is) is presumed for brevity’s sake. I’d like to keep the tone light but we may get into some maths at some point down the line. Maybe you’re thinking about starting your own project and want some guidance or advice? I’m by no means an electrical engineer but perhaps you can avoid some of the same mistakes I’ve made on this journey and use this page as a resource to get your head around the basics.

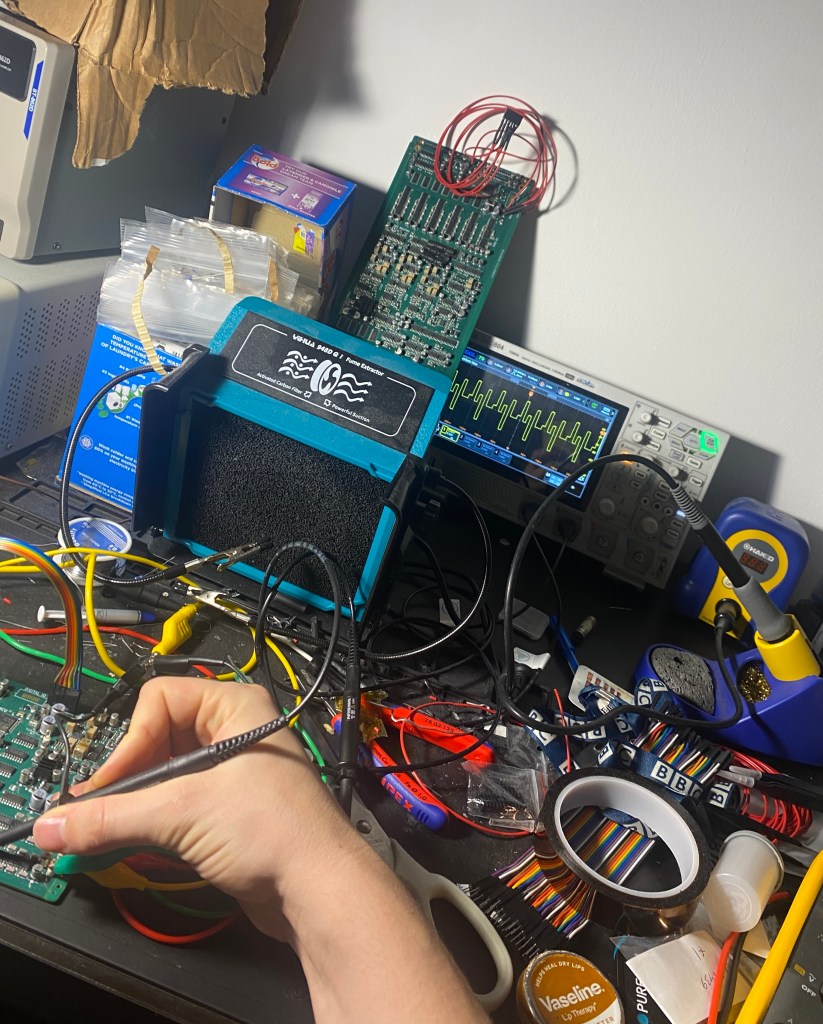

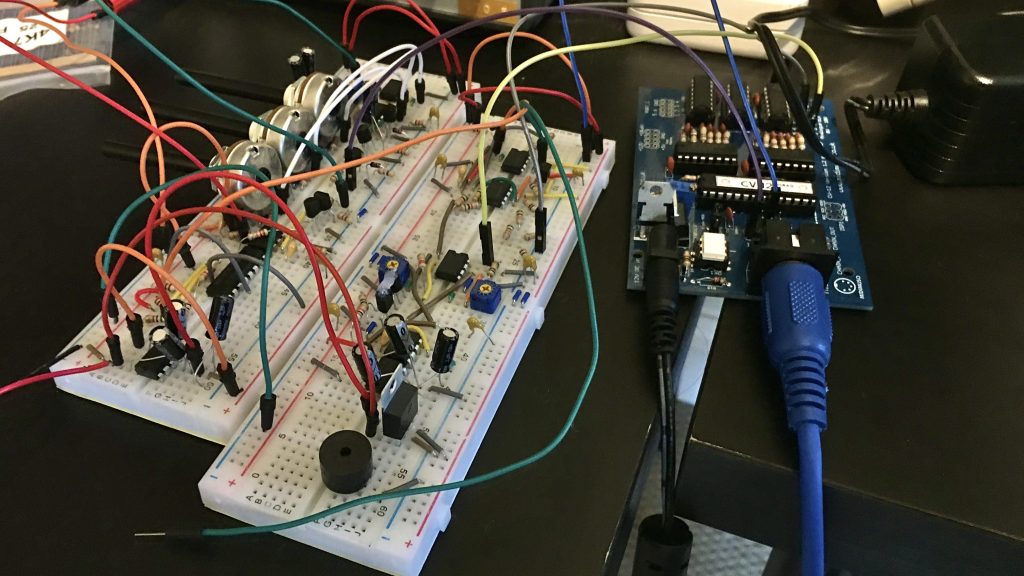

An early monophonic experiment from years past

So what is this synth?

I set out with a fairly simple goal: to build myself a polyphonic synth. I’ve built monophonic synths before at school and college, but it had mostly been on breadboards and I didn’t entirely know what I was doing. This was to be a leap forward. It soon became apparent to me that polyphonic synths are preposterously complex machines with a lot of electronics and generally clever shit going on. As I continued to develop the synth, I realised that if I was going to be bothered to put enough effort in to make the polyphony work, I might as well make the synth as powerful and as feature packed as I could. The specs have changed vastly from the original idea over a year ago and are still being changed slightly but here’s a nerdy spec list in full:

- 16 voices, each with:

- 3x oscillators (saw/pulse/tri/sine)

- 1x sub osc derived from osc1 (saw/square/tri/sine)

- Pink/white/blue noise

- Assignable Hard sync

- Assignable FM

- Assignable Ring mod

- Assignable Wavefolder

- 2x ext input

- 2x analogue ADSR EG (Pitch/filter, filter/amp)

- 1x analogue AR EG for noise contouring

- 2x analogue LFO (multi-wave, and a tri only for vibrato)

- 2x VCF (ladder and state variable)

- 1x VCA

- Each source to be routable to each filter, the Wavefolder, or direct to the VCA

- Global features:

- 2x assignable utility Digital DAHDSR

- 2x assignable utility Digital LFO

- Digital Modulation matrix

- Voice autotune

- Full recall/presets

- Assignable voice allocation

- Split 8/8 voice patches

- Analogue Chorus/drive/delay global effects

- 61 key keyboard with polyphonic aftertouch

- Ribbon controller

- XY pad

- Hardwood case and front panel!

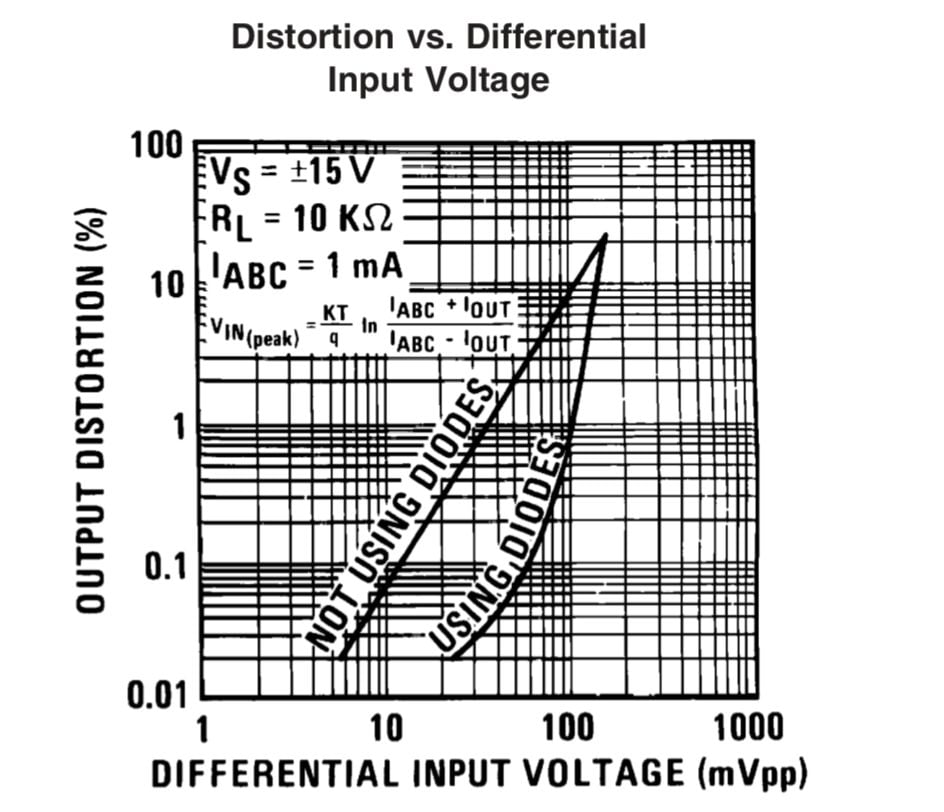

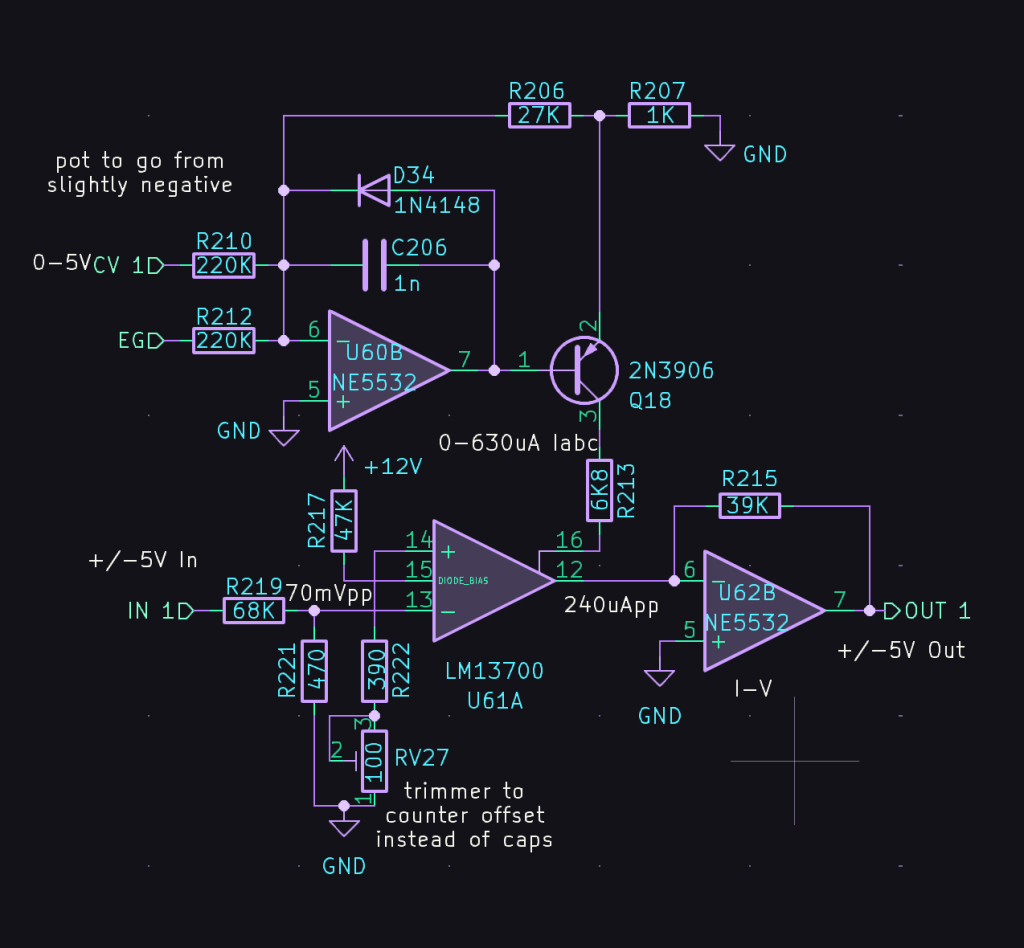

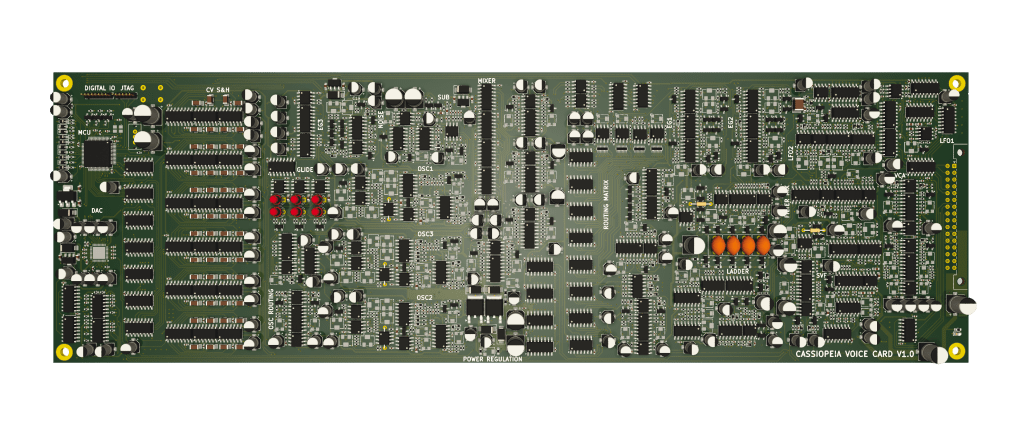

This list is big and expensive. Another obstacle I set myself was not to use any “do it for you” integrated circuits. That includes the AS33xx chips etc found in the prophet 5 and many other poly synths that would simply generate the waveforms or produce an envelope for me. This has to be proper diy otherwise what’s the point of trying to learn how an oscillator works if it’s built into a package for you? I allowed myself simple operational amplifiers, transistors, and transconductance operational amplifiers as well as the shift registers and multiplexers required for the digital side. It seems impractical but actually the voice card is designed and soon to be prototyped. That being said I make a lot of mistakes, and I am far from an electronics guru. I am learning from this process and the main point of this project is as a “thrown in the deep end” learning experience. I may also add a lower manual of 88 keys with monophonic aftertouch but I’ll cross that bridge when I get to it…

Ok then, what’s the overall architechture?

One of the hardest problems with a poly synth (other than tuning oh my god) is that every parameter must be voltage controlled. If you have an 8 voice synth you can’t really have a variable resistor in circuit to tweak a parameter such as the cutoff for a filter as you’d have to have an 8 gang potentiometer which don’t really exist or are prohibitively expensive and impractical. Instead a single voltage can be generated and sent to each control voltage (CV) input on each of the voice cards to somehow drive a change in the behaviour of the circuit. This is achieved in a multitude of ways in practice but rarely is it straightforward and it often adds a variety of additional parts.

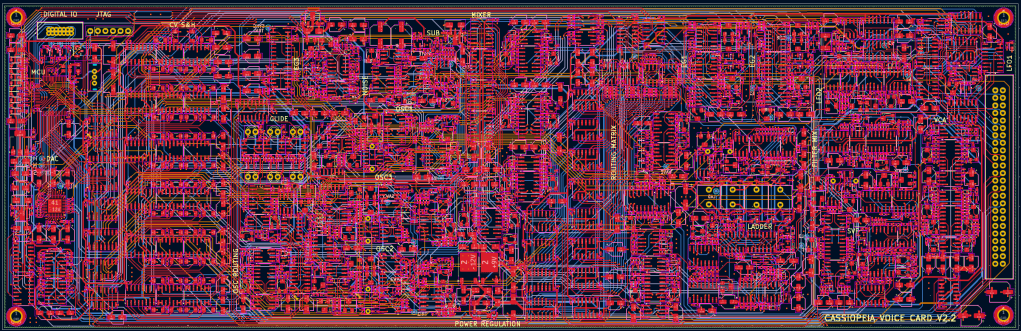

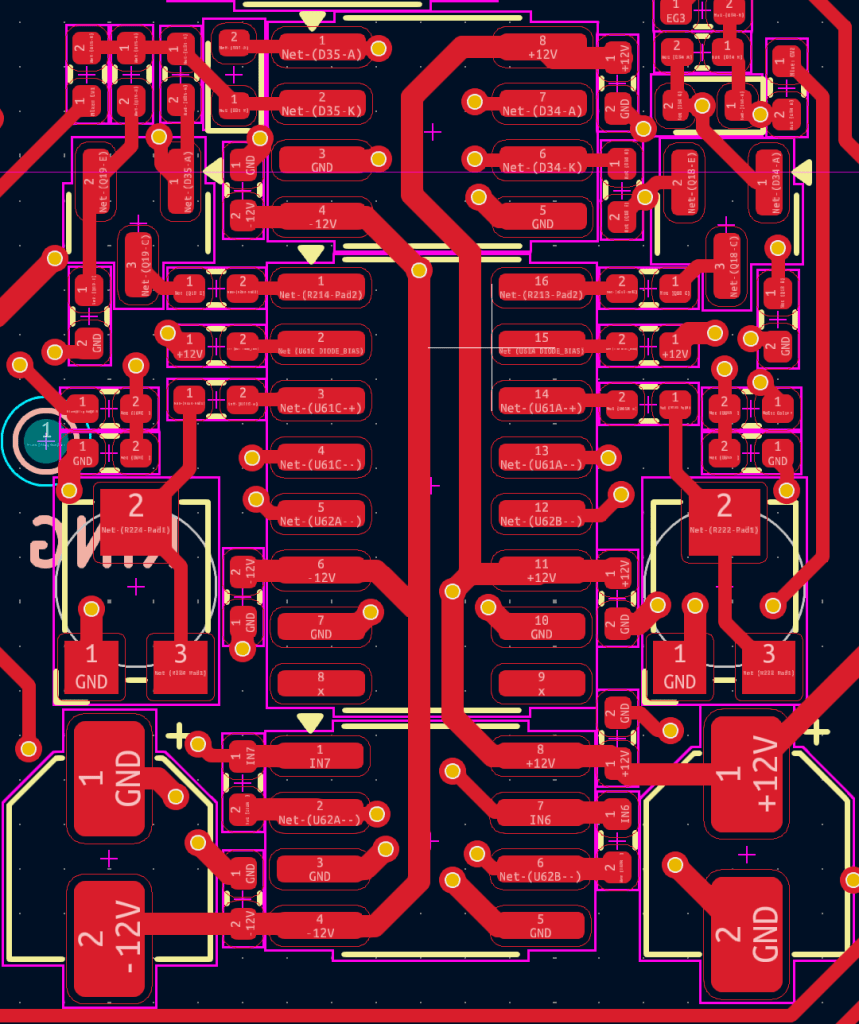

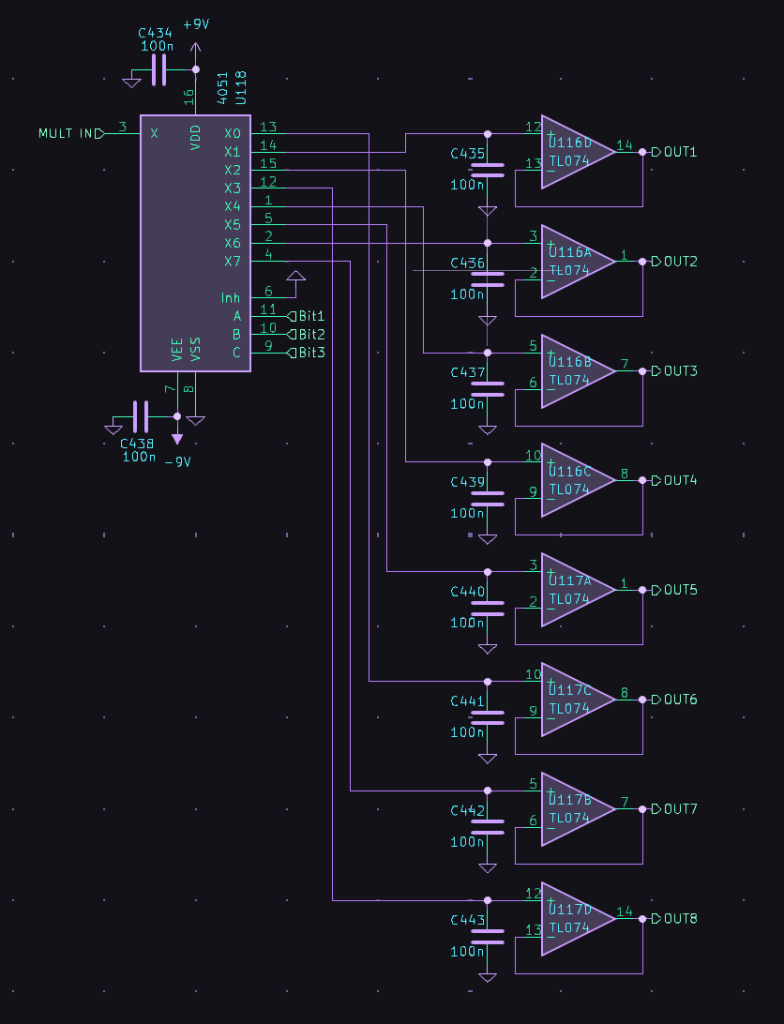

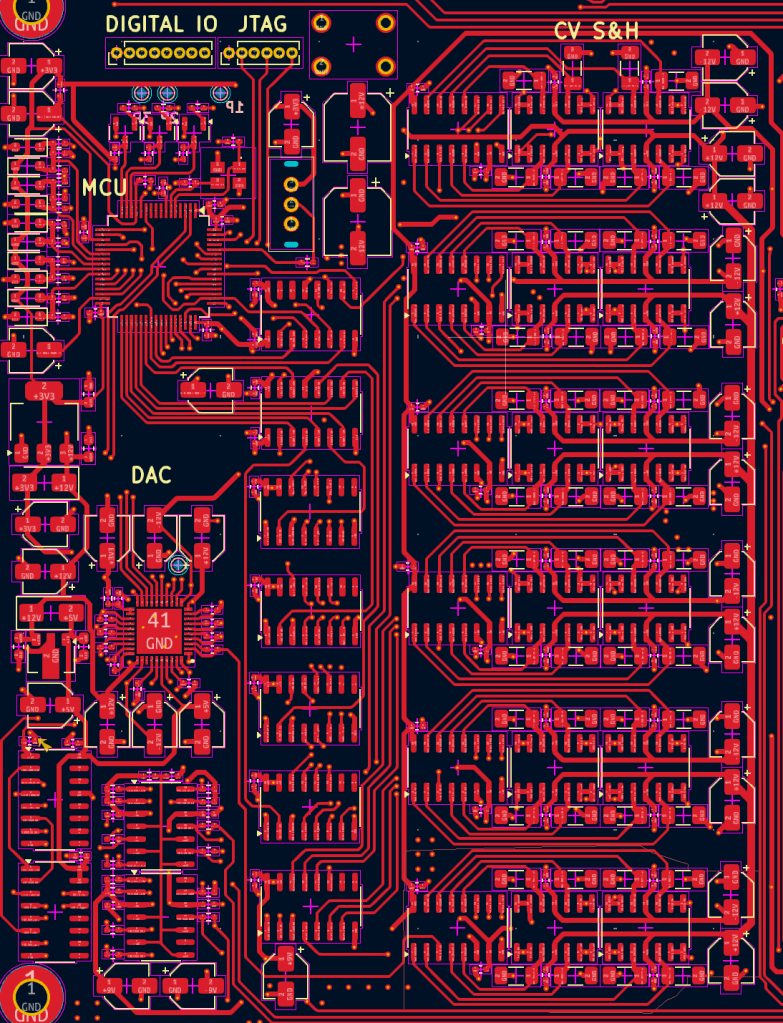

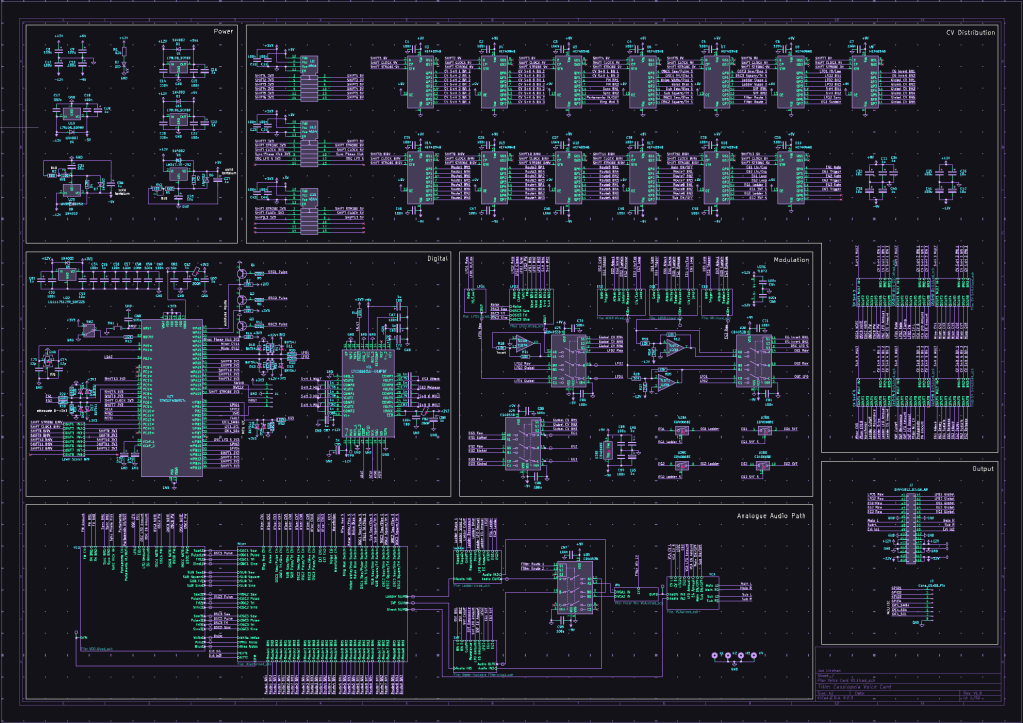

The root page of the voice card schematic. There are many, many sub circuits and additional pages not pictured here.

For my synth I opted to have the front panel with the knobs generate a voltage which is sampled by an analogue to digital convertor (ADC) in a master microprocessor. Once digitised, these voltages are sent digitally to each voice card which has its own local microprocessor. The local MCU then converts back to +/-5V analogue and distributes all the control voltages to various points in the circuit to control parameters. Each voice card audio output is summed on a final board which has the chorus, delay and distortion effects and outputted at line level. Obviously it’s much much more complex once you drill into the nitty gritty and I’ll make a post on each section as I go, but that’s the general idea! This architecture is used in a more or less similar fashion on all polyphonic synths including the Prophet 5, Jupiter 8, Moog One etc etc.

Where am I at currently?

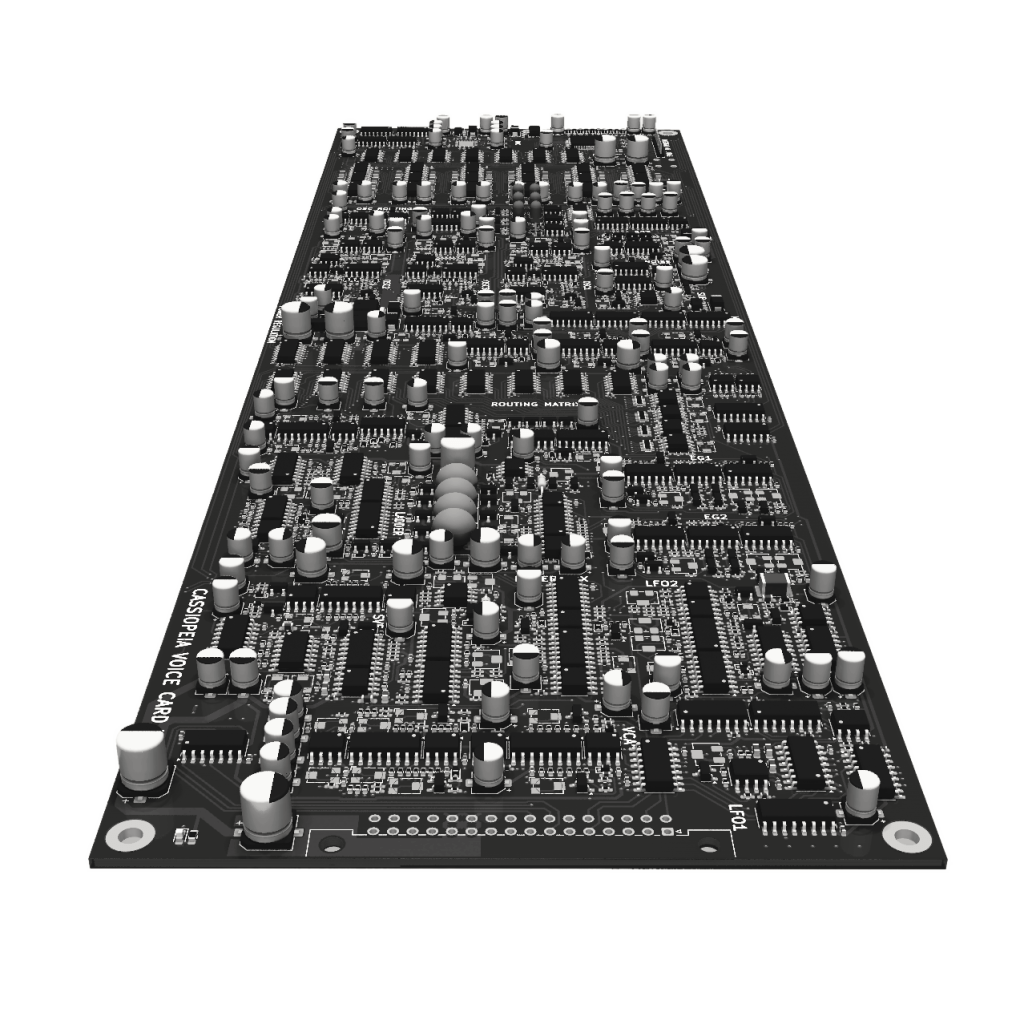

I have spent the last year prototyping and designing the different building blocks of the analogue circuitry and I am currently finalising the first version of the voice card in KiCad. It’s an absolute beast and I don’t expect it to work, but I hope to learn enough from its failure that version 2 might just work! It’s an extremely complex board, at least by my metric and is a 6 layer SMD PCB. I’ll make a separate post on this voice card design at some point in the future. Although the majority of the analogue electronics is complete, there is still much to do and I expect the synth won’t be playable for another few months to a year at least.

Most of the schematics are a blend of things I learnt in books or the internet, trial and error from circuit simulation, and new designs from the top of my head. I’m not an electronic engineer so it’s probably inspired in that order. Many circuits in literature are not designed for poly synths, having potentiometers in the audio path of the circuit. If I do borrow something from somewhere else, often I need to modify the circuit to be voltage controlled, and I tweak a lot of aspects anyway to get the sound or features I want. I’m not trying to reinvent the wheel here, but simply to make a working musical instrument that I might be able to perform with.

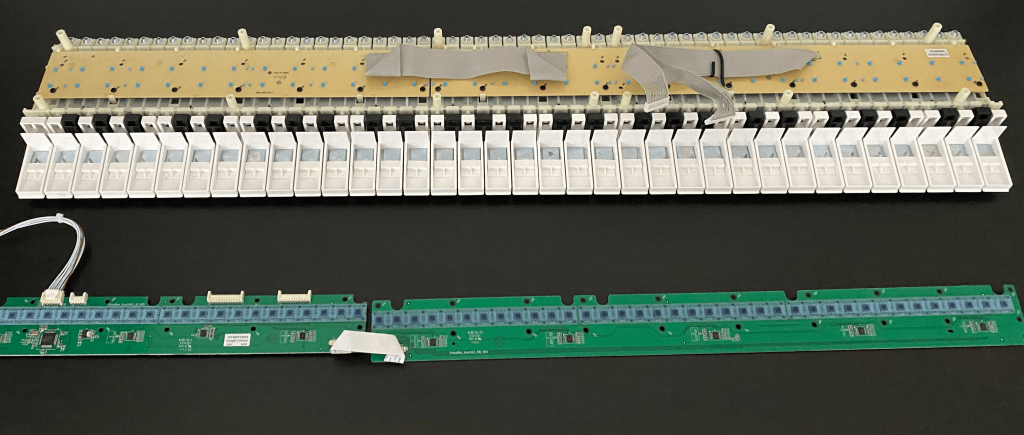

I’ve also bought a keybed which supports polyphonic aftertouch. You would not believe how hard it is to source a keybed like that unless you are an established company, manufacturers just do not want to sell to individuals or let me know anything about the internal mechanisms! After months of trying to source from a supplier, I gave up and bought a Korg Keystage 61. I didn’t want to get too attached to it so almost immediately I took it apart and scavenged it for the keybed and pressure sensors that implement the poly aftertouch. I still haven’t got round to figuring out how to wire it up to my synth, although the keybed has a suspicious wire coming from it labelled UART which I expect is simply MIDI out. As for the pressure sensors, that’s a whole new adventure…

Now that’s plenty of waffle, I think that’ll do for a first post. I doubt many will read this and doubt further that they’d be interested in what I have to say, but on the off chance you are invested, feel free to reach out to my email and ask any questions. Also, I desperately need a name for the damn thing, any suggestions welcome!